L’aventure quantique de Microsoft (2017)

Lors de sa récente conférence Ignite, les dirigeants de Microsoft ont dévoilé que l’entreprise travaillait sur un langage de programmation destiné à un type d’ordinateur qui n’existe pas encore : l’ordinateur quantique. Ce langage a été principalement développé dans son laboratoire Station Q à Santa Barbara, dans lequel Microsoft a beaucoup investi dernièrement : l’effectif a été triplé depuis un an. Il s’intégrera dans Visual Studio et fonctionnera également avec un simulateur quantique.

La nouvelle frontière

Microsoft croit que l’informatique quantique devrait devenir un enjeu technologique majeur au cours des prochaines années. Selon l’analyste Jack Gold, « L’informatique quantique est la prochaine phase en matière de calcul informatique. C’est la nouvelle frontière, et Microsoft veut en être un acteur majeur ».

Quanti… quoi ?

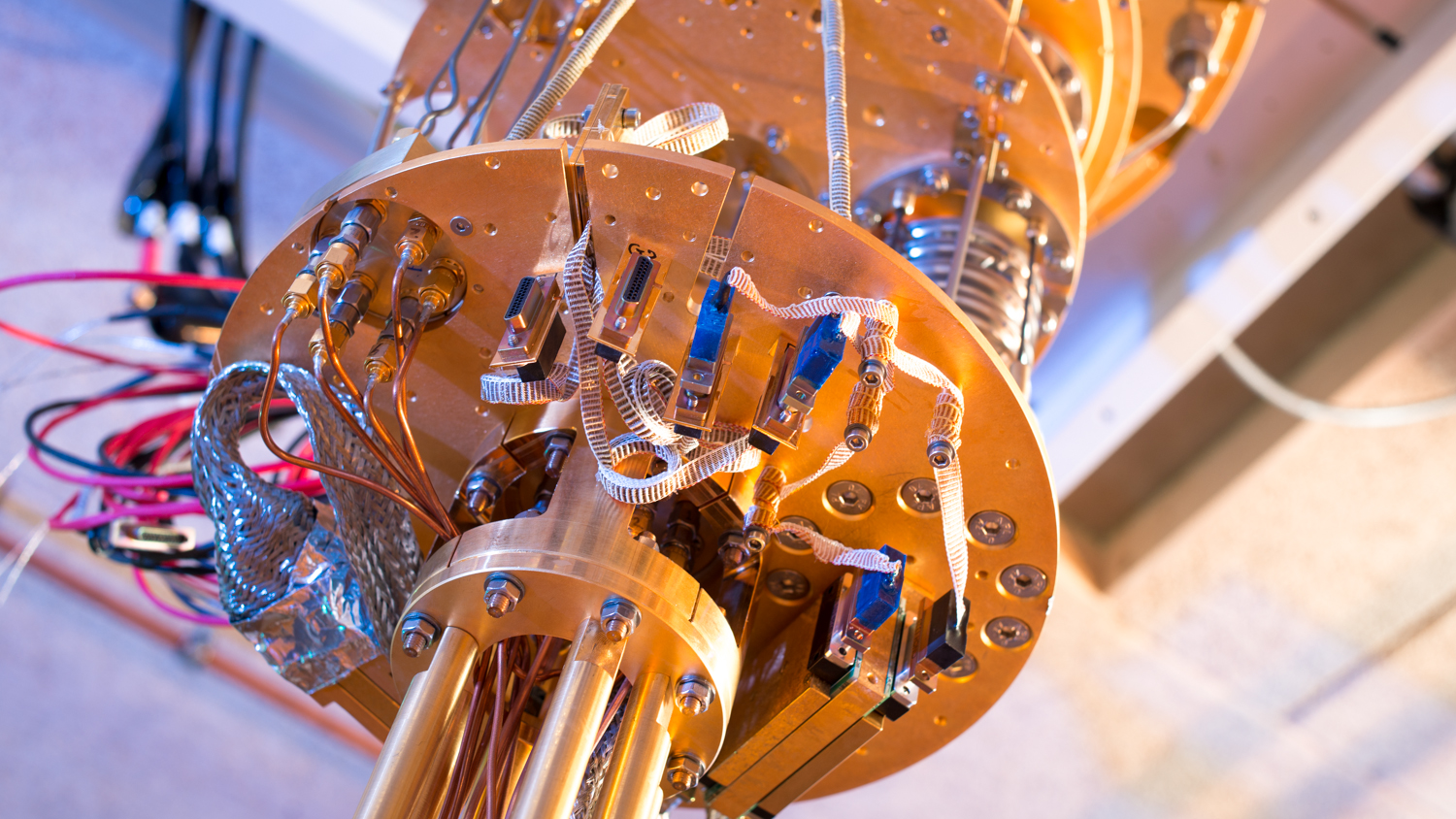

L’informatique quantique est un sujet complexe difficile à appréhender. Disons, en simplifiant beaucoup, qu’au lieu d’encoder l’information sur des transistors en système binaire comme maintenant (les seules valeurs possibles d’un bit étant 0 et 1), on l’encode plutôt dans des bits quantiques, ou qubits. À l’image du bit, le qubit est la plus petite unité de stockage en informatique quantique, mais la différence, c’est qu’il peut stocker deux états quantiques, c’est-à-dire une superposition simultanée d’états. L’avantage d’un ordinateur quantique, c’est que sa puissance de calcul croît exponentiellement à chaque ajout de qubit. Un ordinateur de quelques milliers de qubits permettrait de résoudre des problèmes non accessibles aux calculateurs actuels. Il brillerait en particulier dans la simulation de systèmes complexes.

La particularité de Microsoft

IBM et Google se sont également lancés dans la course, ainsi que plusieurs laboratoires universitaires. La particularité de Microsoft, c’est d’avoir choisi une voie technologique pour fabriquer des qubits qui est plus ardue, mais qui est prometteuse : celle d’encoder de l’information dans des quasi-particules bidimensionnelles appelées des « anyons non-abéliens ». Réussir une percée à ce niveau résulterait probablement en des qubits plus robustes, c’est à dire moins sujets aux interférences (résistants à la décohérence) que ceux des compétiteurs. Le nanomonde est en effet particulièrement sensible aux influences extérieures qui détruisent les fragiles états quantiques.

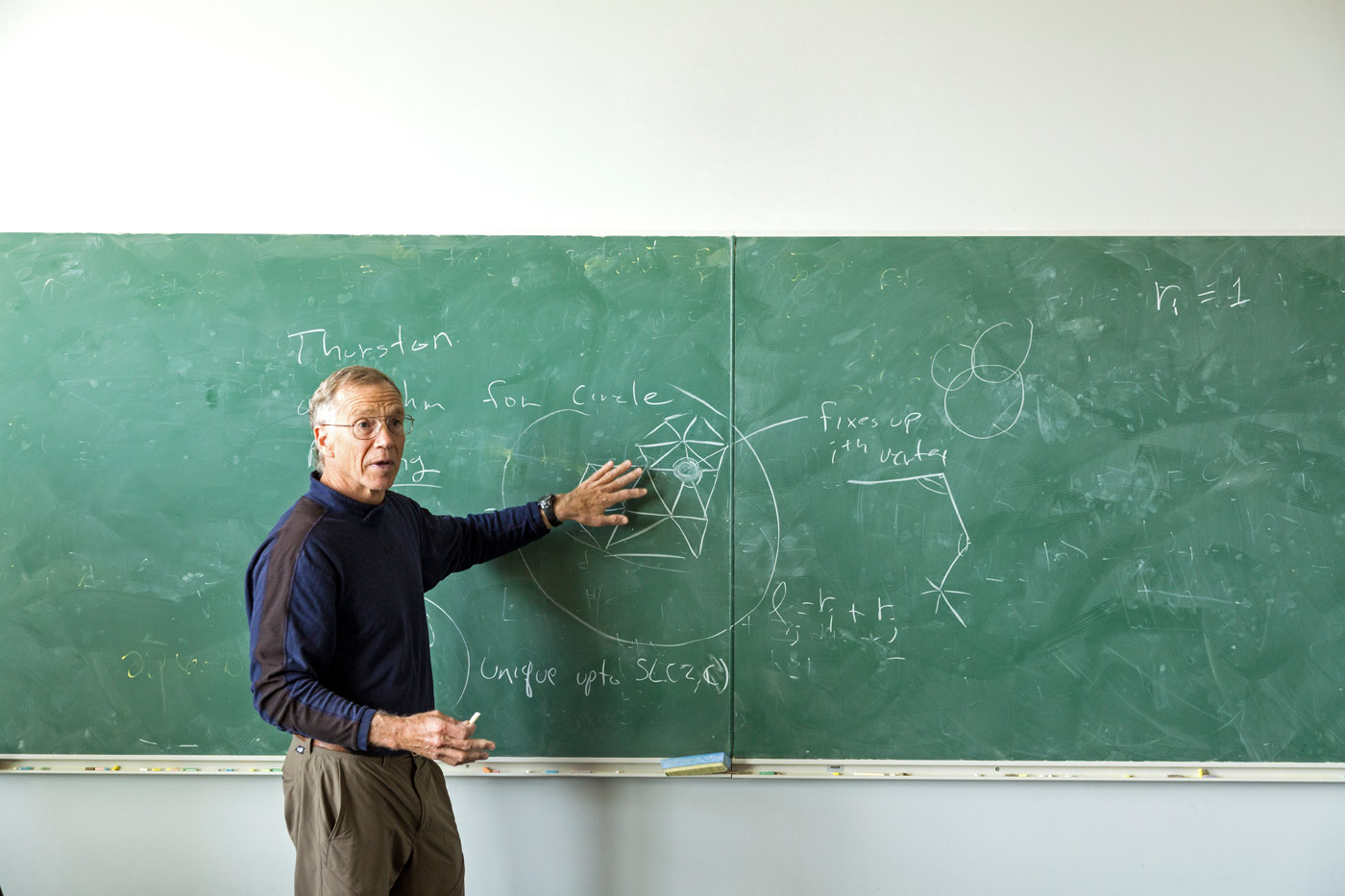

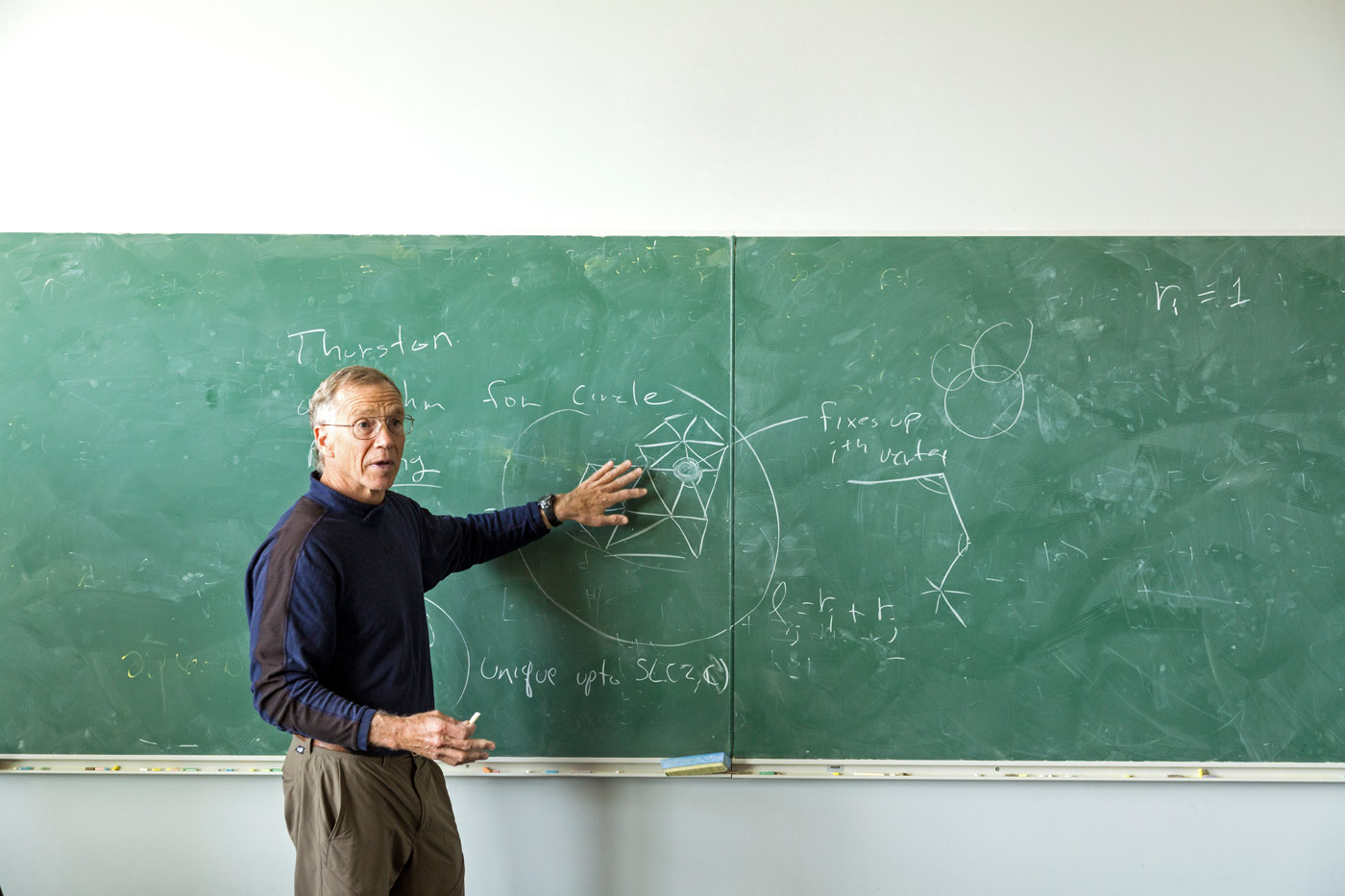

C’est justement cette distinction qui intéresse les analystes et leur fait croire que Microsoft pourrait très bien prendre de l’avance sur IBM, Google et les autres. Il s’agit d’une question de « matière quantique topologique, » basée sur de récentes avancées scientifiques et sur laquelle Michael Freedman, mathématicien de renom et employé de Microsoft depuis une vingtaine d’années, a travaillé. Si vous voulez mieux comprendre l’apport de la topologie à l’informatique quantique, je vous invite à lire l’article de l’Institut Périmètre de physique théorique intitulé “Comment transformer un bagel en un pantalon — et à quoi cela pourrait-il servir”.

Que fera Microsoft de ses nouveaux outils ?

Il est probablement encore trop tôt dans le projet pour établir de manière claire ce que Microsoft voudrait faire d’un éventuel ordinateur quantique : le vendre par lui-même ou encore l’incorporer à Azure, sa solution infonuagique ? Selon Todd Holmdahl, vice-président de la recherche quantique chez Microsoft, même si l’entreprise n’a pas encore tranché, la place la plus logique pour un ordinateur quantique serait justement dans le cloud, entre autres parce que tout ordinateur quantique a besoin d’un ordinateur « classique » pour le contrôler.

Dans un avenir plus rapproché par contre (normalement d’ici la fin de 2017), les développeurs qui le souhaitent pourront faire rouler le simulateur quantique de Microsoft sur leur propre machine (qui devra être plutôt puissante) et se servir du nouveau langage de programmation pour créer des applications. Ce langage emprunte conceptuellement à C#, F# et à Python, ce qui fait dire à différents experts qu’il ne sera pas trop compliqué à assimiler pour quelqu’un avec de bonnes bases en programmation.

« L’idée est de proposer une solution full-stack pour contrôler les ordinateurs quantiques et leur écrire des programmes, » a expliqué Krysta Svore, chercheuse au siège de Redmond.

Et la révolution est pour quand ?

Les experts ne s’entendent pas nécessairement sur l’arrivée de l’informatique quantique. Alors que Jack Gold prédit que certaines applications commerciales pourront arriver sur le marché dans un horizon d’environ 5 ans, Kevin Curran, membre senior de l’IEEE et professeur de cybersécurité à l’Université d’Ulster, prévoit encore une bonne décennie avant que le volume de qubits nécessaires soit atteignable de façon opérationnelle. Charles King, analyste principal chez Pund-IT, est quant à lui plus optimiste : il croit que des systèmes pratiques et utiles verront le jour d’ici 2 à 3 ans. Concernant la solution de Microsoft, il faut savoir que les anyons non-abéliens n’ont pas encore été mis formellement en évidence de façon expérimentale, leur existence étant pour l’instant avant tout théorique.

Si le sujet vous intéresse, le site de Microsoft comporte une section entière sur l’informatique quantique.

Microsoft’s quantum gamble

At its recent Ignite conference, Microsoft announced it had been working on a programming language for a non-existent machine: the quantum computer. The language was mostly developed at Microsoft’s Station Q lab in Santa Barbara, which the company is betting heavily on, having tripled its staff just this year. The language will fully integrate with Visual Studio and be equally at home on a quantum simulator.

A quantum leap

Microsoft believes that quantum computing is the future – now. According to analyst Jack Gold, “Quantum computing is the next phase in computing. It’s the new frontier, and Microsoft wants to be a major player.”

Quant…uhm?

Quantum computing is such a complex concept that few people actually understand it. Dumbing it down, let’s say that, instead of information being encoded on transistors in a binary system, as is the case right now (i.e. each bit can only have one of two possible values, 0 or 1), it is encoded in quantum bits, or qubits. Qubits are the bits of quantum computing, i.e. the smallest unit of storage, the difference being that qubits can be in two quantum states at once, known as a superposition of states. The advantage of a quantum computer is that its computing power grows exponentially with each qubit. This means that a quantum computer with a few thousand qubits can potentially solve problems that current computers just can’t handle, particularly excelling at simulating complex systems.

Microsoft’s wager

IBM and Google have also put stakes in the game, along with several university research labs. But Microsoft chose the riskier and potentially more rewarding way to fabricate qubits: encoding information in two-dimensional quasiparticles called “non-abelian anyons”. If the wager pays off, Microsoft would have more robust qubits which would be far less vulnerable to environmental interference (i.e. resistant to “decoherence”) than those of the competition; the problem with the nanoworld is that it is particularly sensitive to outside influences, which shatter fragile quantum states.

This road less taken is piquing the interest of analysts, leading them to believe that Microsoft could outpace IBM, Google and all the competition. It’s called “topological quantum matter”, and is based on recent scientific advances that Michael Freedman, a renowned mathematician and Microsoft employee for over twenty years, has been working on. To answer your burning questions on the contribution of topology to quantum computing, read the Perimeter Institute’s “How to turn a donut into a pair of pants—and why you might want to”.

How would Microsoft spend its winnings?

It’s too early in the game to know what Microsoft might do with a quantum computer, should it materialize: would it sell the actual machine, or just make it available in Azure, its cloud computing solution? According to Todd Holmdahl, corporate vice-president for quantum research at Microsoft, the company hasn’t decided yet, but the most logical place for a quantum computer is in the cloud, if only because even quantum computers need a classical computer to control them.

On the other hand, in the near future, and maybe as soon as this year, developers will be able to run Microsoft’s quantum simulator on their own (powerful) machines and create applications for it with Microsoft’s new programming language. This language borrows concepts from C#, F# and Python, leading experts to believe that it shouldn’t be too difficult to learn for anyone with a solid programming background.

“The idea here is to offer a comprehensive full-stack solution for controlling the quantum computer and writing applications for it”, said Krysta Svore, researcher at Microsoft’s Redmond HQ.

And when can we expect this new deal?

Experts don’t agree on an exact date for the democratization of quantum computing. Jack Gold predicts that some commercial applications could reach the market within 5 years, while Kevin Curran, a senior member of the IEEE and a professor of cybersecurity at Ulster University, believes it will take at least 10 years to achieve operational volumes of qubits. Charles King, principal analyst at Pund-IT, is more sanguine, predicting practical, useful systems within 2 to 3 years. But coming back to Microsoft’s strategy, the problem is that non-abelian anyons haven’t yet been proven to exist; they are only thought to exist.

To find out more about quantum computing, visit Microsoft’s Web site, with an entire section dedicated to the issue.